A History of Washington, Connecticut

Louise Van Tartwijk, Director of the Gunn Historical Museum

Washington, Connecticut, considered one of the state’s most scenic small towns, is a rural oasis comprised of five “villages” Washington, Washington Depot, New Preston, Marble Dale and Woodville. The town encompasses 38.7 picturesque square miles of rolling hills, dramatic vistas, quiet forests, and abundant waterways. Washington’s natural landscape, combined with the small town feel of its shopping centers and quaint town Green provide its inhabitants with a unique quality of life, that has consistently drawn entrepreneurial, creative and hardworking people to the area.

The Shepaug River, meaning “rocky river” in the Eastern Algonquin language, has shaped the story of Washington. The Shepaug divides the town in half as it winds southward to eventually merge with the Housatonic River and empty into Long Island Sound. Archaeological excavations conducted by the Institute for American Indian Studies have established that Washington was inhabited over 10,000 years ago. These early people made their homes near the fertile river, which provided a rich and continual source of food that included a variety of plants, animals and fish. The eastern and southern portions of Washington were Pootatuck Indian homelands, while the Weantinok tribe inhabited the western and northern portions. Lake Waramaug, which means “good fishing place” in Eastern Algonquin, was named after one of the grand sachems of the Weantinock.

Washington Green in 1886

The first Europeans to enter the Washington area came from the coastal town of Stratford in 1673 and used the Housatonic, Pomperaug and Shepaug rivers as water highways to lead them into the northern wilderness. These original settlers, fifteen Stratford men and their families, headed up river to establish a new community as a result of irreconcilable religious differences with the Stratford church. They had been granted permission to erect a plantation (as early settlements were called) on lands purchased from Chief Pomperaug of the Pootatuck Indians. This area later became the towns of Woodbury, Southbury, Middlebury, South Britain, Bethlehem, Roxbury and Washington. In 1734 Joseph Hurlbut became the first settler to build a home in what is now Washington, and the Congregational Church became the founding institution of the town in 1743, originally named Judea.

The colony of Connecticut played an important role in the War for Independence and a number of Judea’s prominent citizens saw action in such battles as Germantown, Monmouth, Yorktown and the taking of Fort Ticonderoga. The graves of thirty of Judea’s Revolutionary War veterans can be found in the Judea Cemetery. During the course of the war, General George Washington passed through the area several times and spent a night at the Cogswell Tavern (now a private home) in the village of New Preston. In 1779, when the town became incorporated, it was decided to change the name from Judea to Washington in honor of the Continental Army’s Commander-In-Chief.

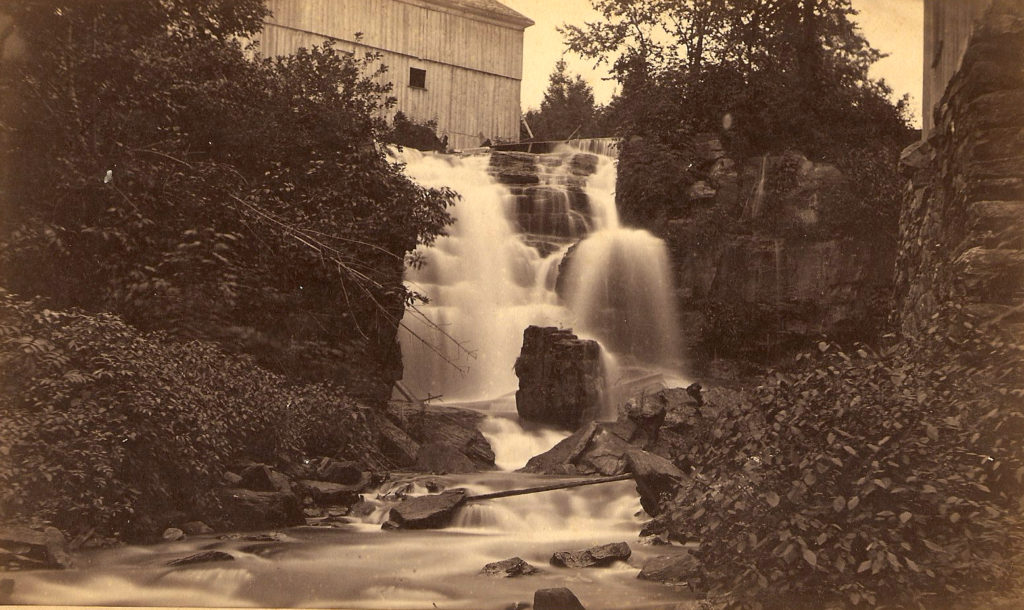

Washington began as an agrarian farming community, remnants of which can be found today in the ruins of stonewalls, many of them now partially hidden in woodland. These are reminders that for a great many years, Washington was mostly open land, the trees cleared for farming, or put to use as timber for building or for the making of charcoal to fuel the iron forges. The first major industrial enterprise in Washington was established in 1746 by Edward Cogswell, who secured the right to mine ore and established an iron works along the East Aspetuck River in New Preston. This led to the rapid appearance of several other shops and factories along the same river that included saw and grist mills, an iron furnace, a yarn, twine and cotton batting factory, a sleigh shop, a tannery and a harness shop. New Preston’s industrial activity thrived for many years until it fell behind other industrial centers that had converted to steam power and had better access to rail transportation.

The early businesses of Washington literally turned on water. Water-wheel-powered mills of varying kinds appeared all along Mallory Brook, Bee Brook, and Kirby Brook. Anywhere there was flowing water, small-scale milling industries could be found. During this time, the Shepaug River attracted a proliferation of mills along its banks. And what had previously been known as Washington Hollow became Factory Hollow. The Titus Mills were one of the earliest to use the Shepaug’s waters and produced lumber for use in local construction and furniture making. By 1871 the Titus Mills had passed into the ownership of Henry Woodruff, who expanded the operation into a 3-story factory that housed the Washington Match Company and a wagon making shop later known as the Kingman Mills.

In 1872, the Shepaug Valley Railroad arrived in town, transforming Washington into a regional dairy center and a summertime retreat for wealthy New Yorkers. The Shepaug Railroad ran between Hawleyville in the south to Litchfield in the north, traversing 32 very crooked miles, passing through a rock tunnel and crossing the Shepaug River six times. The train prompted yet another name change and Factory Hollow became Washington Depot which swiftly grew into a bustling business hub with blacksmiths, hardware stores, pharmacies, banks, bookstores, carpenters, clothing stores and much more. The Borden Creamery employing 100 people and producing cheese, butter and other dairy products soon turned Washington Depot into Connecticut’s milk shipping station, sending out 12,000 quarts a day in the 1880’s. The Borden factory was a great boon to local farmers and dairy farming became the primary industry in Washington from 1880 – 1920. The Borden Factory closed in 1928 and the Bryan Memorial Town Hall was built on the site in 1932.

Washington Depot flood of 1955.

The arrival of the railroad meant that it was suddenly possible to travel from New York to Washington in just a few hours time. As a result Washington, because of its bucolic charm, became a popular destination for a unique group of creative and wealthy philanthropic families from New York City, especially Brooklyn Heights. Many of these individuals had been educated by Frederick Gunn at the Gunnery School, on the Washington Green, and shared a romanticized view of the relationship between man and nature. These sentiments were heightened by the changes that rapid industrialization was bringing across America, triggering a nostalgic longing for an idealized version of America’s past known as the Arcadia Movement. On and around the Washington Green, these individuals found a way to create their own idyllic summer colony with the goal being to preserve a rapidly disappearing way of life. This “return to Arcadia” was accomplished through the building of impressive shingle-style country homes or “cottages” designed by architect Ehrick Rossiter; the creation of the Gunn Memorial Library and History Room and the adding of Colonial Revival architectural touches to existing buildings on The Green. At the same time, the small shops and businesses located on The Green were removed, a golf course was established, an elegant holiday retreat for young women working in New York’s factories was founded, and a nature reserve known as Steep Rock was created through Ehrick Rossiter’s purchase of 100 acres of woodland.

The Washington Green, with its churches, schools, residences, and shops had been the center of town until the arrival of the railroad. St. John’s Episcopal Church in 1815, relocated to the Green from its earlier location in Davies Hollow, eventually joined the Congregational Church on the hill. Across the Green from the churches, was and still is, Washington’s longest operating school. Established in 1850, The Gunnery was named after its founder, Frederick Gunn, educator, abolitionist, lover of the out-of-doors and recognized “father of recreational camping.” From the beginning the school accepted girls as well as boys and developed a reputation with notable Litchfield and Brooklyn Heights-based families such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and her brother Henry Ward Beecher both of whom sent their children to be educated there.

The Shepaug Railroad passed into the history books in 1948 after years of debt finally caught up with it. It was not the demise of the Shepaug railroad, however, that had the biggest negative impact on Washington’s economy. That came, suddenly and ferociously on August 19th, 1955, when the Shepaug River swollen to a raging torrent by the waters of two hurricanes, flooded Washington Depot with a wall of water that swept away shops homes and bridges. The destruction was enormous and the National Guard and Army Corps of Engineers were called in to help the Depot dig out and rebuild. The re-construction effort became controversial as the loss of so many buildings to the floodwaters gave rise to a large-scale re-building plan. Spear-headed by Henry Van Sinderen, the plan called for replacing the lost 18th and 19th century wooden homes with modern 1950s red brick buildings intended for retail; the bulldozing of buildings that had escaped the flood’s destruction and the re-locating of others. While this plan was eventually award winning, it drastically changed the original character of Washington Depot, sacrificing private homes and walk-ability for the accommodation of the automobile and an increase in retail shops.

Washington’s identity has been shaped over the centuries by the various people who have called it home, studied at its schools, worshipped in its churches, and run its businesses. Washington has changed with the times and yet has still been able to preserve its original authenticity and integrity. The buzz of mill saws may no longer be heard on New Preston’s main street, but the former mini-industrial center has become a quaint upscale shopping destination. Washington Depot is no longer a train stop, but the Depot remains Washington’s business center. Brooklynites and other city dwellers continue to flock to “Arcadia” to enjoy the unique quality of life it offers. Today, Mr. Gunn’s school is still on the Washington Green, and three other private schools have been established in town making education Washington’s biggest business.

The history of Washington is one of continuity coupled with the acceptance of change, and nothing symbolizes this better than the Shepaug River. The river no longer needs to provide essential food for those who live along its shores, but it has become critical habitat for a number of endangered local species. The river no longer functions as a water highway for settlers, nor is its waterpower essential for Washington’s businesses, but the river remains a cherished natural resource. Today, most of Washington’s Shepaug River flows through what is the now nearly 3,000 acres of the Steep Rock Preserve, where the natural pristine river’s beauty is protected for all to enjoy. The Shepaug River is, and always has been, at the core of Washington’s identity and its flowing waters link the town’s past to its future.

Sources used:

Bader, William: An American Village: The Light at the North End of the Tunnel, 1998

Carlson, Einar & Howell, Kenneth: Empire Over the Dam 1974

Clark, Howard: Saga of Pomeraug Plantation, 1973

Cothren, Wiiliam: History of Ancient Woodbury, Connecticut, 1854

Gilchrist, Alison: Return To Arcadia, 2006

Howell, Kenneth: From the Pootatick Indians to the Indian Diggings at Kirby Brook Site in Washington, Ct. 1971

Krimsky, Paula: Reading, Writing & the Great Outdoors: Fredereick Gunn’s School Transforms Victorian Education.

Lind, Brenda & Caroline Norden: Steep Rock and the Shepaug; The Land and the River through Time. 1986

Special thanks to Lucianne Lavin of the Institute for American Indian Studies